Research Methods in Psychology Chapter 5 Review Questions

Chapter 7: Nonexperimental Research

Correlational Research

- Ascertain correlational inquiry and requite several examples.

- Explicate why a researcher might choose to conduct correlational enquiry rather than experimental research or some other blazon of nonexperimental inquiry.

What Is Correlational Research?

Correlational research is a type of nonexperimental research in which the researcher measures ii variables and assesses the statistical relationship (i.e., the correlation) betwixt them with little or no effort to control extraneous variables. There are essentially 2 reasons that researchers interested in statistical relationships between variables would choose to conduct a correlational study rather than an experiment. The starting time is that they practice not believe that the statistical relationship is a causal one. For example, a researcher might evaluate the validity of a cursory extraversion test by administering it to a big grouping of participants along with a longer extraversion exam that has already been shown to exist valid. This researcher might then bank check to see whether participants' scores on the cursory examination are strongly correlated with their scores on the longer one. Neither exam score is thought to cause the other, so there is no independent variable to manipulate. In fact, the terms independent variable and dependent variable do not apply to this kind of research.

The other reason that researchers would choose to utilise a correlational study rather than an experiment is that the statistical relationship of interest is thought to exist causal, only the researcher cannot manipulate the independent variable because information technology is impossible, impractical, or unethical. For example, Allen Kanner and his colleagues thought that the number of "daily hassles" (east.g., rude salespeople, heavy traffic) that people feel affects the number of physical and psychological symptoms they take (Kanner, Coyne, Schaefer, & Lazarus, 1981). [ane] But because they could non dispense the number of daily hassles their participants experienced, they had to settle for measuring the number of daily hassles—along with the number of symptoms—using cocky-report questionnaires. Although the strong positive human relationship they found between these two variables is consequent with their idea that hassles crusade symptoms, it is also consistent with the idea that symptoms crusade hassles or that some third variable (e.m., neuroticism) causes both.

A common misconception among starting time researchers is that correlational research must involve two quantitative variables, such as scores on two extroversion tests or the number of hassles and number of symptoms people have experienced. However, the defining feature of correlational research is that the two variables are measured—neither ane is manipulated—and this is true regardless of whether the variables are quantitative or categorical. Imagine, for example, that a researcher administers the Rosenberg Cocky-Esteem Calibration to fifty American university students and l Japanese university students. Although this "feels" like a between-subjects experiment, it is a correlational study because the researcher did not dispense the students' nationalities. The same is truthful of the study past Cacioppo and Trivial comparing professors and factory workers in terms of their need for cognition. Information technology is a correlational written report because the researchers did non manipulate the participants' occupations.

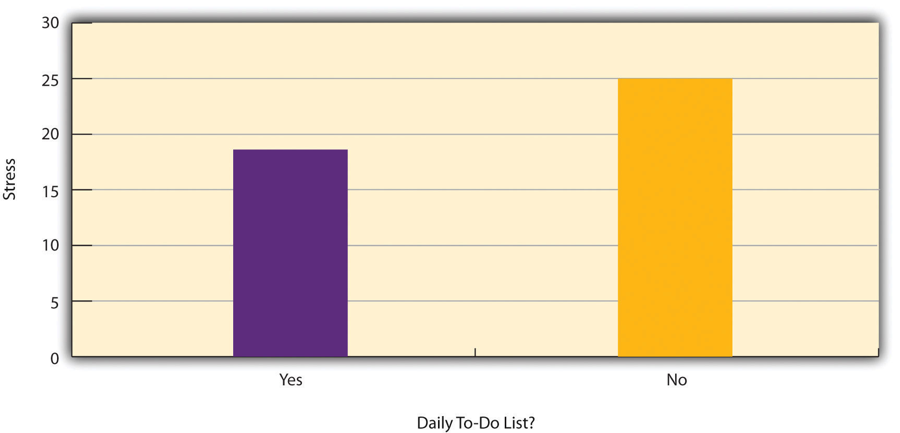

Figure 7.2 shows data from a hypothetical study on the relationship between whether people make a daily list of things to do (a "to-do list") and stress. Notice that information technology is unclear whether this design is an experiment or a correlational study because information technology is unclear whether the independent variable was manipulated. If the researcher randomly assigned some participants to make daily to-exercise lists and others not to, then it is an experiment. If the researcher only asked participants whether they made daily to-do lists, then it is a correlational written report. The distinction is of import because if the report was an experiment, then information technology could be concluded that making the daily to-practice lists reduced participants' stress. But if information technology was a correlational study, it could only be concluded that these variables are related. Perchance being stressed has a negative consequence on people's ability to programme ahead (the directionality trouble). Or maybe people who are more conscientious are more than probable to make to-do lists and less likely to be stressed (the third-variable trouble). The crucial point is that what defines a written report as experimental or correlational is non the variables being studied, nor whether the variables are quantitative or categorical, nor the type of graph or statistics used to clarify the information. It is how the study is conducted.

Data Collection in Correlational Enquiry

Once again, the defining feature of correlational research is that neither variable is manipulated. It does non thing how or where the variables are measured. A researcher could have participants come to a laboratory to complete a computerized backward digit span task and a computerized risky controlling task and and then assess the human relationship between participants' scores on the two tasks. Or a researcher could become to a shopping mall to ask people near their attitudes toward the environment and their shopping habits then assess the relationship between these two variables. Both of these studies would be correlational because no independent variable is manipulated. However, because some approaches to data drove are strongly associated with correlational enquiry, information technology makes sense to talk over them here. The two we will focus on are naturalistic observation and archival data. A tertiary, survey research, is discussed in its own affiliate, Affiliate 9.

Naturalistic Ascertainment

is an approach to data drove that involves observing people's behaviour in the surroundings in which it typically occurs. Thus naturalistic observation is a type of field enquiry (as opposed to a type of laboratory research). It could involve observing shoppers in a grocery store, children on a school playground, or psychiatric inpatients in their wards. Researchers engaged in naturalistic observation usually make their observations as unobtrusively every bit possible then that participants are frequently not aware that they are beingness studied. Ethically, this method is considered to be adequate if the participants remain anonymous and the behaviour occurs in a public setting where people would non unremarkably have an expectation of privacy. Grocery shoppers putting items into their shopping carts, for example, are engaged in public behaviour that is easily observable past store employees and other shoppers. For this reason, near researchers would consider it ethically acceptable to find them for a study. On the other hand, one of the arguments against the ethicality of the naturalistic observation of "bathroom behaviour" discussed before in the book is that people accept a reasonable expectation of privacy fifty-fifty in a public restroom and that this expectation was violated.

Researchers Robert Levine and Ara Norenzayan used naturalistic ascertainment to study differences in the "pace of life" across countries (Levine & Norenzayan, 1999). [2] One of their measures involved observing pedestrians in a large city to run into how long information technology took them to walk 60 feet. They establish that people in some countries walked reliably faster than people in other countries. For example, people in Canada and Sweden covered lx feet in just under xiii seconds on average, while people in Brazil and Romania took shut to 17 seconds.

Because naturalistic observation takes identify in the complex and even chaotic "real earth," there are ii closely related issues that researchers must deal with before collecting data. The get-go is sampling. When, where, and nether what conditions will the observations be fabricated, and who exactly will be observed? Levine and Norenzayan described their sampling process equally follows:

"Male and female person walking speed over a distance of sixty feet was measured in at to the lowest degree two locations in primary downtown areas in each city. Measurements were taken during main business hours on clear summer days. All locations were apartment, unobstructed, had broad sidewalks, and were sufficiently uncrowded to permit pedestrians to motion at potentially maximum speeds. To command for the effects of socializing, only pedestrians walking solitary were used. Children, individuals with obvious physical handicaps, and window-shoppers were not timed. Thirty-5 men and 35 women were timed in near cities." (p. 186)

Precise specification of the sampling process in this way makes information collection manageable for the observers, and it also provides some command over important extraneous variables. For case, by making their observations on articulate summertime days in all countries, Levine and Norenzayan controlled for effects of the weather condition on people'south walking speeds.

The 2d outcome is measurement. What specific behaviours volition be observed? In Levine and Norenzayan'due south study, measurement was relatively straightforward. They simply measured out a 60-foot distance along a urban center sidewalk and then used a stopwatch to time participants as they walked over that distance. Oftentimes, however, the behaviours of interest are not and then obvious or objective. For example, researchers Robert Kraut and Robert Johnston wanted to written report bowlers' reactions to their shots, both when they were facing the pins and and then when they turned toward their companions (Kraut & Johnston, 1979). [3] Just what "reactions" should they detect? Based on previous research and their own airplane pilot testing, Kraut and Johnston created a list of reactions that included "closed smile," "open smile," "laugh," "neutral face," "look downwards," "look away," and "face cover" (covering one's face with one's hands). The observers committed this list to memory and and then practised by coding the reactions of bowlers who had been videotaped. During the actual study, the observers spoke into an audio recorder, describing the reactions they observed. Among the most interesting results of this written report was that bowlers rarely smiled while they nevertheless faced the pins. They were much more than likely to smile subsequently they turned toward their companions, suggesting that grinning is not purely an expression of happiness but besides a form of social communication.

When the observations crave a judgment on the role of the observers—as in Kraut and Johnston's study—this procedure is oftentimes described as . Coding generally requires clearly defining a set of target behaviours. The observers then categorize participants individually in terms of which behaviour they have engaged in and the number of times they engaged in each behaviour. The observers might even record the duration of each behaviour. The target behaviours must exist defined in such a way that different observers code them in the same mode. This difficulty with coding is the issue of interrater reliability, as mentioned in Affiliate five. Researchers are expected to demonstrate the interrater reliability of their coding process by having multiple raters code the same behaviours independently then showing that the unlike observers are in close agreement. Kraut and Johnston, for case, video recorded a subset of their participants' reactions and had two observers independently code them. The two observers showed that they agreed on the reactions that were exhibited 97% of the time, indicating skilful interrater reliability.

Archival Data

Another approach to correlational research is the use of , which are information that take already been collected for another purpose. An instance is a written report by Brett Pelham and his colleagues on "implicit egotism"—the tendency for people to prefer people, places, and things that are like to themselves (Pelham, Carvallo, & Jones, 2005). [4] In i study, they examined Social Security records to show that women with the names Virginia, Georgia, Louise, and Florence were especially likely to have moved to us of Virginia, Georgia, Louisiana, and Florida, respectively.

Equally with naturalistic ascertainment, measurement can be more or less straightforward when working with archival information. For case, counting the number of people named Virginia who alive in various states based on Social Security records is relatively straightforward. But consider a study by Christopher Peterson and his colleagues on the relationship between optimism and health using data that had been nerveless many years before for a study on adult development (Peterson, Seligman, & Vaillant, 1988). [5] In the 1940s, healthy male college students had completed an open-ended questionnaire about difficult wartime experiences. In the late 1980s, Peterson and his colleagues reviewed the men's questionnaire responses to obtain a measure of explanatory mode—their habitual ways of explaining bad events that happen to them. More than pessimistic people tend to arraign themselves and expect long-term negative consequences that affect many aspects of their lives, while more optimistic people tend to blame outside forces and expect express negative consequences. To obtain a mensurate of explanatory style for each participant, the researchers used a procedure in which all negative events mentioned in the questionnaire responses, and whatever causal explanations for them, were identified and written on index cards. These were given to a separate group of raters who rated each explanation in terms of three divide dimensions of optimism-cynicism. These ratings were then averaged to produce an explanatory style score for each participant. The researchers then assessed the statistical relationship between the men's explanatory style as undergraduate students and archival measures of their health at approximately 60 years of age. The primary result was that the more optimistic the men were as undergraduate students, the healthier they were as older men. Pearson'south r was +.25.

This method is an example of —a family unit of systematic approaches to measurement using complex archival data. Simply as naturalistic observation requires specifying the behaviours of involvement and then noting them as they occur, content assay requires specifying keywords, phrases, or ideas and then finding all occurrences of them in the information. These occurrences can and then exist counted, timed (eastward.g., the corporeality of time devoted to entertainment topics on the nightly news show), or analyzed in a diverseness of other ways.

- Correlational research involves measuring two variables and assessing the relationship between them, with no manipulation of an independent variable.

- Correlational research is non defined by where or how the data are collected. However, some approaches to data drove are strongly associated with correlational inquiry. These include naturalistic observation (in which researchers discover people's behaviour in the context in which it normally occurs) and the use of archival data that were already collected for another purpose.

Word: For each of the following, decide whether information technology is well-nigh likely that the study described is experimental or correlational and explain why.

- An educational researcher compares the academic performance of students from the "rich" side of town with that of students from the "poor" side of town.

- A cognitive psychologist compares the power of people to call up words that they were instructed to "read" with their ability to recall words that they were instructed to "imagine."

- A manager studies the correlation between new employees' higher grade betoken averages and their showtime-yr operation reports.

- An automotive engineer installs different stick shifts in a new auto epitome, each time asking several people to rate how comfortable the stick shift feels.

- A food scientist studies the relationship betwixt the temperature inside people's refrigerators and the amount of leaner on their food.

- A social psychologist tells some research participants that they need to hurry over to the adjacent building to complete a written report. She tells others that they can take their fourth dimension. Then she observes whether they stop to assistance a research assistant who is pretending to be injure.

Source: https://opentextbc.ca/researchmethods/chapter/correlational-research/